A small collection of the amazing creatures that we share this earth with!

Orchid Mantis

The orchid mantis (pictured) looks deceptively like the bloom of a moth orchid. In addition to having a pink and white body with just the right patterns, it will sway gently to mimic the effect of wind on the petals. When a prey insect buzzes by to look for nectar, the mantis rapidly strikes. For more than a century, this species and a few relatives have been iconic examples of animal mimicry.1

Fireflies

One of my favorite beings.

The light of a firefly is a chemical reaction caused by an organic compound – luciferin – in their abdomens. As air rushes into a firefly’s abdomen, it reacts with the luciferin. Consequently, it causes a chemical reaction that gives off the firefly’s familiar glow. This light is sometimes called cold light because it generates so little heat.2

See also: Firefly photography.

Peacock Mantis Shrimp

Imagine this dazzling display beneath the waves: A sudden burst of light, a lightning-quick strike of its claws that can cut to the bone and even shatter glass. These profoundly powerful pint-sized predators boast reflexes speedier than a seagull snatching your beach snacks. Depending on the morphology of their claws, they adeptly spear or smash their targets, effortlessly cracking open snail shells or pulverizing prey with precision. The peacock mantis shrimp (Odontodactylus scyllarus), notorious for its astonishingly powerful punch, clocks in a striking speed of an impressive 60 miles per hour.3

That’s all the reality TV I ever need.

Salmon

Scientists believe salmon navigate by using the earth’s magnetic field as a form of compass, which they use to retrace their route to the river they came from. After finding the right river, they use smell to guide their way back to their home stream, according to the United States Geological Survey. ^[https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2024/04/04/chinook-spring-smolt-crash-river/]

Spiders

By releasing a silky sail, the crawlers can “balloon” far distances—sometimes over entire oceans. See how they catch the wind.

It turns out spiders may be some of nature’s best little pilots.

Using a technique called “ballooning,” they release sail-like trails of silk that lift them up and off into the wind. In some cases, they drop just a few feet from their takeoff site; in others, they get caught in jet streams that take them across oceans. In all cases, they go where the wind takes them.

…

Before takeoff, the spiders prepared, like any good pilot would do.Sticking out a front, hairy leg, the spiders tested wind speeds. In his lab, Cho was able to manipulate speeds and found that the spiders typically didn’t take off until speeds were lower than three meters per second.4

Velella

Image by Zhengan - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=89603666

Though they look like one organism, velella – also known as by-the-wind sailors – are actually colonies of creatures from a class called hydrozoa that use the wind to speed along. They spend most of their lives out in the open ocean, searching the water column below them with tentacles that sting fish larvae or zooplankton, but are harmless to humans. One part of the colony is responsible for eating, another for reproduction.

…

Velella live for months and travel widely around the Pacific gyre, says Julia Parrish, a marine biologist at the University of Washington. Typically they travel down the coast of California to Central America, then shoot out past Hawaii to Japan and return again, skimming along the surface like a kite surfer. ^[https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/apr/05/blue-tide-west-coast-beaches]

Watch: The secret life of Velella: Adrift with the by-the-wind sailor

Mudskippers

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CAQuoH_fOWM

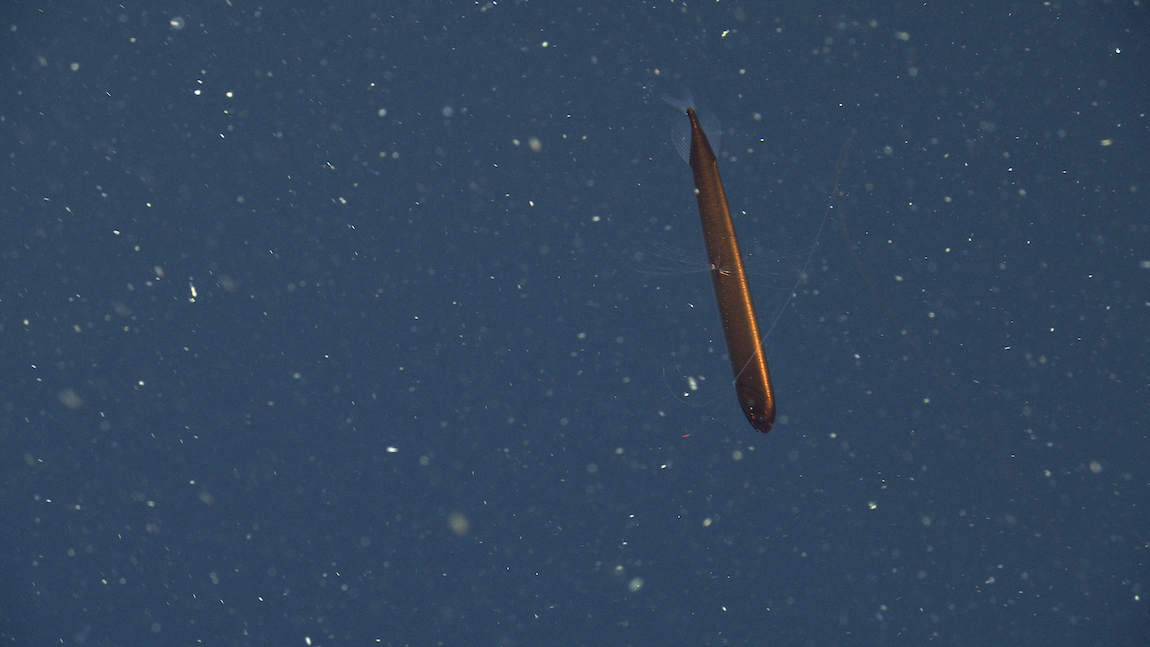

Highfin Dragonfish

Highfin dragonfish (Bathophilus flemingi) - Monterey Canyon • 303 meters (994 feet) • Image: © 2022 MBARI, https://www.mbari.org/wp-content/uploads/Bathophilus_flemingi_D1431_03_1150.jpg

The Bathophilus flemingi, also known as the highfin dragonfish, was captured on video by a team of researchers in Monterey Bay, California. Named after the mythical creature, the torpedo-shaped fish is a predator that roams the depths of the ocean.

The fish can grow up to 16.5cm in length and has long thin rays for fins. Scientists think the wing-like filaments can detect vibrations and can alert the fish of oncoming predators and prey.

The dragonfish uses a sit-and-wait tactic in which it hangs motionless in midwater and waits for unsuspecting crustaceans and fish to feed on, according to the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI). It also uses a bioluminescent filament that extends from its chin. ^[https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/may/06/california-rare-deep-sea-fish-monterey-bay]

And, the Blackbelly Dragonfish (Stomias atriventer)

Image: © 2003 MBARI

Cicadas

*Photo by Ashlee Marie.

Periodical cicada nymphs spend years underground growing and feeding off fluid from the roots of plants. When their time to emerge arrives, they tunnel upward, wait for the soil temperature to reach about 64 degrees and then crawl to the surface, en masse, within a few weeks.

Once aboveground, the plump nymphs inch their way up the nearest vertical surface — a tree, a fence post, a person standing very still — where they molt one last time, spread their wings and spend the last weeks of their lives desperately trying to mate.

The males develop their signature sound, a loud high-pitched, high-decibel buzz that ideally will attract females. The noise can be overwhelming, but other than that, cicadas are not harmful to humans. ^[https://www.washingtonpost.com/science/2024/01/26/cicada-brood-map/]

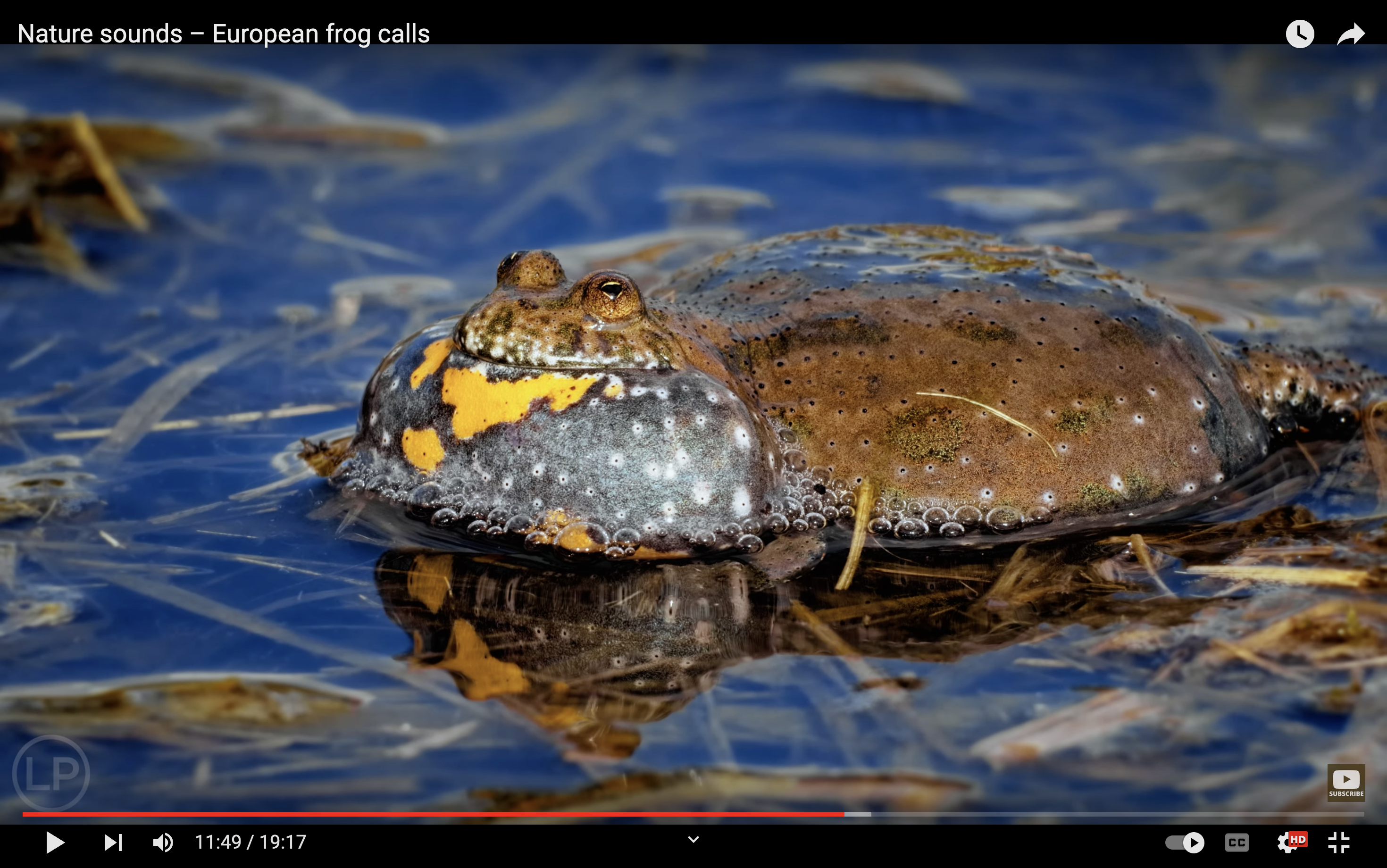

Frogs!

Watch this incredible close-up video with frog calls feat. the kooky Marsh Frog and others.

Marsh frog (Pelophylax ridibundus):

Moor frog (Rana arvalis):

European fire-bellied toad (Bombina bombina) makes an incredible haunting song. (listen)

Snails

Footnotes

-

https://www.science.org/content/article/winged-legs-orchid-mantis-sets-gliding-record ↩

-

https://earthsky.org/earth/fireflies-light-up-why-how/#:~:text=The%20light%20of%20a%20firefly,off%20the%20firefly’s%20familiar%20glow. ↩

-

https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/stories/meet-the-mantis-shrimp ↩

-

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/spider-silk-ballooning-flying-animals-spd ↩